Pingyao: Ancient walled city

MUCH has been said about Shanxi’s ancient walled city of Pingyao, home of China’s earliest bank, the Rishengchang founded on the premises of a dye shop in 1823 to service the province’s Jinshang (Shanxi merchants). Jin was, of course, the name of the state that flourished in the area nearly three millennia ago during the Zhou dynasty and remains the short name for Shanxi.

Before Rishengchang, transactions were paid for in silver, coins or other valuables which had to be escorted by armed guards. This time-honoured practice ended when the bank began taking silver deposits and replacing currency with bank drafts, a move which consigned the armed “security services” to the martial arts novels, TV serials and movies that immortalise the extinct trade.

The draft bank’s success owed much to the then-revolutionary business practice of separation of ownership and management which led to greater professionalism, as well as to a strict emphasis on integrity supported by a system of rewards and penalties.

Looking at Rishengchang’s modest premises in Pingyao, one would never have guessed the scope of its business. At its peak, the bank had deposits totalling 20 million liang (tael) of silver and handled remittances amounting to 38 million liang. With branches in key cities and trade centres, it flourished for 108 years until it ceased draft banking in 1932 to focus on savings and loans, and eventually collapsed in the face of competition from western-style banks.

A plaque at the establishment’s courtyard says there were altogether 22 such draft banks in Pingyao, making the city the undisputed financial centre of China during the last century of the Qing dynasty.

Pingyao is a living museum of Ming and Qing dynasty architecture and like the province’s Yungang grottoes near Datong, is a Unesco World Heritage site. Our group arrived in the early evening and given the walled city’s historic importance, it came as a surprise that the portion of highway near Pingyao was dark and in poor condition.

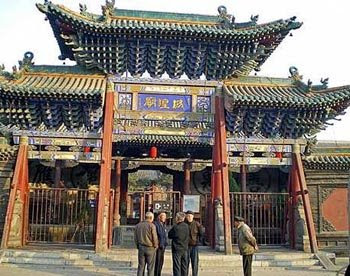

Peasants with cartloads of hay and produce paid scant attention to safety as we bumped and jolted along for what seemed like ages until we arrived at the city’s famed battlements. From there we transferred to open buggies, winding our way around the massive Ming dynasty walls to our hotel on a street of refurbished two-storey linked courtyard residences near the Chenghuangmiao (Temple of the City God).

The rooms around the deep courtyard had been converted into guestrooms of different sizes with custom furnishings and modern attached bathrooms.

Some accommodations looked quite cosy, but I passed an uncomfortable night in a tiny bare room lit by a single fluorescent tube. Like the other rooms, a traditional woven bamboo mat hung outside the door provided added privacy.

Attached to a closet-like bathroom, my “cell” might have been the watchman’s or maid’s quarters. The only furniture included two narrow brick kang beds and a small wooden table with a TV. Lined with a thin cotton quilt, the kang had been decommissioned and was no longer heated from underneath like an oven.

The old architecture and lanes within Pingyao’s city walls have been preserved and some areas were in fact cordoned off for on-going restoration work. The city folk are seemingly used to strangers poking around their homes and when I meandered into a residential quarter, a friendly woman welcomed me into her courtyard and proudly pointed out her neighbour’s house whose windows had been beautifully refurbished.

In the streets and shops around Rishengchang, craftsmen continue to ply their trade for the benefit of tourists, most of whom are from other provinces. Shanxi has a rich tradition of crafts such as colourful shoe linings hand-embroidered with motifs like fish, frogs and flowers, and hand-made cloth shoes and wooden combs. Traditional melt-in-your-mouth pounded peanut candy and crispy stone-baked crackers flavoured with sesame, spring onions or spices are also hot favourites.

The Jinshang played such an important role in the province’s commercial history that a whole section of the new Shanxi Museum in Taiyuan is devoted to them. In one of the very smart galleries, there is an interesting specimen of a Rishengchang deposit book and bank licences from the Qing dynasty. Reconstruction of several of these Pingyao banks’ premises show that for all their wealth, the bankers operated in rather spare surroundings.

The museum also has a section on that Jinshang favourite – Shanxi’s vernacular Jin opera. Acts from two different operas are projected onto a black screen the size of a large television, providing visitors a mesmerizing glimpse of this exotic art form.

Pingyao and the surrounding counties formed the heartland of the Jinshang clans whose intrepid, enterprising members were quick to spot new opportunities and boldly ventured wherever there were business prospects. The clans may be gone, but it is said the Jinshang’s innate talent for business still runs in the blood of many Shanxi people today.